Issue 4: Hidden Voices

Behind the Brand of James Bond

Elizabeth Nichols

In order to explore hidden aspects of popular Western visual culture, I will turn to the character of James Bond and the actor who currently portrays him, Daniel Craig. A plethora of marketing campaigns and advertisements surround this character, all of which rely on the image of the character to sell their particular product. To examine how the Bond brand endeavours to create a connection between products and certain traits of the main character, it is necessary to understand how Daniel Craig is constructed as the image of Bond. A company forms its identity through branding; a strong brand helps to construct a consistent message and a loyal following. Usually, companies create an image that goes alongside the brand, for example the Nike ‘Swoosh.’ However, in the case of products linked to the Bond brand, a separate image cannot really be created as there is an actor who portrays the character on screen. If a separate image was created it would cause a sense of disruption between the actor who portrays the character on screen and the image that is tied to the brands themselves. As a result, the Bond brand uses the image of Daniel Craig to endorse the products that are linked to it and in effect turns him into a silenced representative for the James Bond brand. It is in this way that Daniel Craig also becomes a branded cultural object. To examine how this branding process takes place this article will outline how brands in general are created and then move on to how the Bond brand has been constructed around the image of Daniel Craig.

According to Lash and Lury, ‘cultural objects are everywhere; as information, as communications, as branded products, as financial services, as media products, as transport and leisure services, cultural entities are no longer the exception: they are the rule’ (4). A cultural object is an item, such as a watch or sportswear, which has become a symbol and as such can be used in the creation of a brand. Cultural objects have become ‘subsumed in homogenous units, each one identical to the next’ (Lash and Lury 7) and culture no longer consists of things that are totally unique. Instead, a series of brands are consumed, a process that suggests the cultural superstructure is collapsing into the material base as the economy becomes more cultural and as goods become more informational. Brands are vital in this process; ‘the notion of the brand that has been developed is that it is the dynamic organisation of a system of relations between products… Attention was drawn to the processes of personalisation and the ways in which logos may be seen as the face of the brand’ (Lury 2004 82). Brands are not immediately identifiable in everyday life. Instead it is ‘a face – that is, the logo or logos – [that] make the brand visible’ (Lury 2011 74). Indeed, for a brand to be a success it has to be supported by an image. It is the logo that functions as a device for ‘magnifying one set of associations and then another, creating a set of associations in the mind of the consumer’ (Lury 2004 80). Lury extends this argument by stating that the brand is not immaterial, neither is it fixed in time or space but rather it is the platform for the patterning of activity. What I will be examining is how the brand is a happening fact in that it actively creates certain types of meaning to go along with the products that are associated with it.

Ours is an increasingly ‘visual world, a world in which we are bombarded every day and everywhere with images’ (Thomas 1), particularly in the form of photographs which are much more readily available than painting or sculpture. Consumers are presented with images continuously on the internet, on buses, posters, on our phones and in countless other forms. As a result of this, images are used to extend our way of seeing as they open up new possibilities of experience. According to Rosalind Coward, the ‘camera in contemporary media has been put to use as an extension of the… gaze’ (33). If something cannot be seen directly, it can be looked up and viewed as a photograph or image. The outcome of this is that photographs give people an imaginary possession, that which they do not posses, and viewing the desired object close up gives the viewer the illusion of owning it themselves. This perhaps is due to the fact that, as Roland Barthes states, when something is photographed it can never be denied that ‘the thing has been there’ (58) and this goes on to create within an individual a sense of ‘certainty that such a thing had existed’ (Barthes 60). There is a connection between the viewer and the object as a ‘sort of umbilical cord links the body of the photographed thing to [the] gaze’ (Barthes 60) of the observer. Barthes claims that the same connection does not apply with cinematic images as in that medium something ‘has passed in front of this same tiny hole’ and as such the object is ‘swept away and denied by the continuous series of images’ (Barthes 59). However, it can be argued that cinema has more of an impact than an individual image as the audience is being bombarded with a greater variety of images and so is more susceptible to their influence as a result. Part of this comes from the use of sound in film in addition to visual images. As Prince notes, film ‘needn’t be restricted to visual information; cinema is a medium of picture and sound’ (191). It is the added aspect of sound which ‘can impact powerfully on the reality and atmosphere of a setting’ (Oumano 27). Viewing images and understanding their meaning does not rely solely on the act of looking but on decision-making, as our brains search for the best possible interpretation of the available data. This interpretation is a form of cultural decoding, giving the audience a sense of participation and strengthening the connection between them as an individual and what is being shown on the screen.

The focus of Lash and Lury’s argument about branding looks at images in terms of operations, and the ways in which images direct us in how they should be lived out. Cultural objects that are encountered in images become immersed in everyday lives. For example, ‘movies become computer games… brands become brand environments, taking over airport terminal space and restricting department stores, road billboards and city centres… cartoon characters become collectibles and costumes… music is played in lifts, part of a mobile soundscape’ (Lash and Lury 8). Viewers are presumed to be at once historically innocent and purely receptive as well as being immediately susceptible to images. However, advertising companies rely on the intelligence of the consumer to pull a succession of different images together in order to interpret a single one correctly. The importance of visual images ‘might appear to be the effect of a culture which generally gives priority to visual impact rather than other sensual impressions’ (Coward 33).

It is this reliance on the viewer which enables product placement to be so effective. It is not simply the case that an audience is shown a series of products and told to go and buy them; objects are scattered throughout the film and it is left to the viewer to notice them or not. In the Bond films, and most notably in Casino Royale (2006), there is an abundance of product placement where advertisers have paid to have their product included. By examining James Bond instead of an individual object, it is possible to see how brands sometimes act like windows and doors. That is to say: they are not closed systems but are capable of incorporating other aspects into themselves, which allow them to expand and grow:

The brand, constituted in its difference, generates goods, diversified ranges of products. The commodity is determined from outside: it is mechanistic. The brand is like an organism, self-modifying, with a memory (Lash and Lury 6).

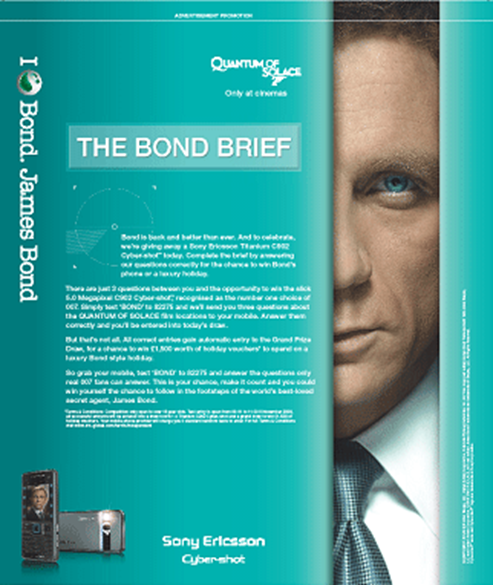

Figure 1: The Bond Brief (2010)

A commodity is an individual item, whereas the brand incorporates several commodities into itself in order to expand its customer base and allow for a deeper understanding into the identity of the brand. In the case of James Bond, it is possible to see how his persona is created using a range of products. These products are used to help create an image to reinforce this assumed identity. In order to understand how Daniel Craig, as an individual, is effaced from this process, it is necessary to first discuss how the products are tied both to the character and to the films.

Even before an actor takes up the role of Bond, the brand is firmly in place. Products link themselves to the James Bond franchise because it has come to represent a variety of things: sophistication, wit, refinement, charisma and ruthlessness. The companies then present their products in such a way to engender these feelings in the audience who view their advertisements. Through close analysis of the advertisement it is possible to examine how the Sony Ericsson mobile phone creates certain emotional responses by linking the product directly to James Bond (see Figure 1). As well as the section of Daniel Craig’s face placed down the right hand side of the advertisement, the advert includes the title of the film, Quantum of Solace (2008) to enable us to establish the connection between the product and the film. The text on the advert reflects all the characteristics that are associated with the character of James Bond. The phone is extolled as a ‘natural fit with the cool, sophisticated style of James Bond’ (‘The Bond Brief’). When the statement ‘a man who doesn’t do things by half-measures’ (‘The Bond Brief’) is placed there the implication is that when you purchase the phone you will take on the same attributes. The branding of James Bond is such a success partly because he is spoken about as if he is a real person and not merely a character. This comes through as the reader is told that the ‘exclusive new camera phones enable the world’s most famous secret agent to stay on top of the action with exactly the same sense of style and performance as Sony Ericsson phones bring to everyday life’ (‘The Bond Brief’). The consumer encouraged to believe that if they buy the phone then they will acquire the style and persona of James Bond. The important thing here is how the advert never uses the name Daniel Craig, but instead emphasises the link to James Bond. Even though the advertisement shows Daniel Craig’s face, he is not seen as an actor but instead as James Bond. This is how the actor becomes lost behind the image of the brand he is representing. The situation is paradoxical since it is the face of the actual actor that brings the immaterial brand to life.

Lury explains how logos serve to make the brand visible (2004 74). The logo, or actor’s face in this case, serves as a device ‘for magnifying one set of associations and then another, creating a set of associations in the mind of the consumer’ (Lury 2004 80). The films and the products attached to them are the material that the spectator is presented with, and paying increased attention to the material actually demands that the real force of the immaterial is taken seriously. The immaterial is the brand attached to specific films and also the actors who become brand representatives in their associations with those films. There are, of course, fundamental differences between a brand and a product: ‘the commodity is produced. The brand is a source of production... The commodity has no history; the brand does… The commodity has no memory at all; the brand has memory’ (Lash and Lury 6). In this case, the brands deploy a person instead of a logo and, in doing so, transform that particular person and their everyday movements into a branded body. This makes it easier to associate certain products with a particular brand as the image used for them all is the same. The importance here is the person that they have chosen to represent the brand, rather than choosing a random model these brands have selected a specific celebrity to represent their products. Featherstone speaks of the ‘aura, charisma or presence’ (194) of Hollywood celebrities as an ‘ineffable quality that [is] felt rather than seen’ (194). For Omega, the actor Daniel Craig as a representation of their brand is the most important thing: it is imperative that they hire him because he plays James Bond. In Casino Royale, the focus on Omega is brought to the fore in an exchange between Bond and Vesper Lynd (Eva Green):

Vesper Lynd: MI6 only hire SAS types with easy smiles and expensive watches. [Glances at his wrist] Rolex?

James Bond: Omega.

Vesper Lynd: Beautiful.

Though this very brief interchange, the product is tied both to the film and the character. The Omega webpage dedicated to James Bond emphasises his character:

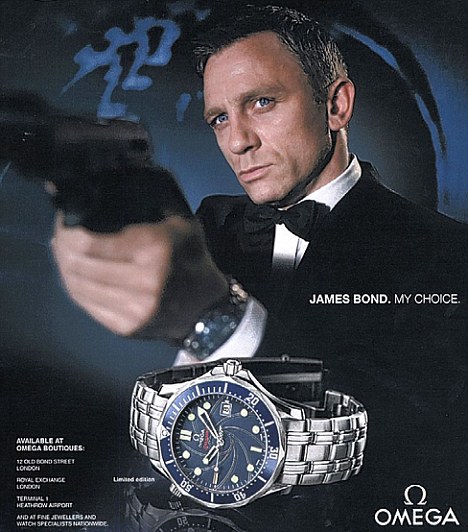

Figure 2: Omega and Bond (2014)

The picture shows us a calm and ruthless looking Bond; he is depicted in a more casual way as he is without his black blazer but still sophisticated as it is possible to catch a glimpse of his Omega watch while he straightens his tie. The advertisement does not present the consumer an image of Daniel Craig; the gun strap he is wearing makes it clear that this is James Bond. The use of James Bond in Omega advertising encourages brand loyalty not simply to an individual product or company, but to the brand of James Bond. There is a certain authority held within the character that is carried across from the films, which means that as the consumer accepts fewer brands they become more loyal to the brands that Bond is the representative of. This is because all the products that are tied to the character of Bond carry the same message: if you buy the product then you too will become as stylish and sophisticated as James Bond.

Figure 3: 'James Bond Celebrates 50th Anniversary' (2012)

When products move out of a film to stand on their own, they are viewed differently. Products often go unnoticed when they are embedded within a film; it is only when the advert draws a parallel with a specific film that it becomes obvious and the product is depicted in a new way. Brands are not made up of the qualities of products: they are constructed through qualities of experience. As was illustrated with the advertisement for the Sony Ericsson phone (Figure 1), the consumer is presented with a certain type of experience, represented by James Bond, which is made attainable through the suggestion that all that needs to be done is to purchase the product to receive the promised experience.

After building up the brand through the films, the persona of the character the audience is presented with comes to the fore and the actor is forced into the background:

Figure 4: 'Hand over your wristwatch, 007' (2011)

When one actor takes over the role of Bond, they are immediately placed into the advertising campaigns so that, in the run up to a film, they become the face of that brand and are, therefore, synonymous with it. With a franchise such as James Bond, this could be seen as a necessary thing to do. Since several actors have played the same role, the audience need to believe that the new actor will be able to fulfil the role and respond to the demands of the character. Keeping the actor tied to the franchise that they are representing means that there is a definitive link created between the fiction of the film and the reality that lies outside of the film: ‘it smashes the illusion that there is a meaningful distinction in modern society between illusion and reality, fact and fantasy, fake and genuine images of self’ (Bowlby 34). The advertisements break down these boundaries for the viewer through the use of repetition; it is possible to get so used to seeing Daniel Craig as James Bond until eventually he is not seen as himself at all. Figures 3 and 4 illustrate how Daniel Craig is tied to the brand of James Bond over and over again. In Figure 3 the consumer is shown Daniel Craig’s Bond front and centre in an advert for Skyfall (2012). Similarly, in Figure 4, the picture of Bond is the main focus for the viewer. The text in both the advertisements also helps when it comes to hiding Daniel Craig. Figure 3 has ‘Bond is Great Britain’ in large, bold letters on the left (‘James Bond celebrates 50th Anniversary’), whilst Figure 4 states ‘James Bond. My Choice’ (‘Hand over your wristwatch 007’). The close proximity of the text in both cases to the image of Daniel Craig encourages a viewer to understand that the text is referring to the actor as James Bond. In Figure 3 it makes sense to use Daniel Craig as he plays the main character in the film, however, the second advert (Figure 4) was released in a year when there was no Bond film to promote. Since merchandise, such as the Omega watch, is linked to the Bond Brand, then the use of Daniel Craig in adverts outside of promotional materials for the film is also prolific. While he is James Bond, Craig is confined to the limits which that brand imposes on him. He is consistently used as he has come to represent the Bond brand; to stop using him as the main image would diminish the overall brand experience. Latham and McCormack describe the ‘material variously as the actual… in opposition to the immaterial, the abstract and unreal’ (704). This idea can be extended into the idea of brands, as the brand experience is a feeling, not a concrete perception. Rather than being something tangible that can be looked at or touched, the brand is instead the experience of intensity and so, in this sense, a form of virtual experience. When it comes to the selling of goods, the focus is on the promotion of brands rather than specific products. It is essential to think about the brand as not being localised, but spread across a wide array of products. The focus is not on the products and goods that a certain company sells but on the personal culture that they are offering through their products.

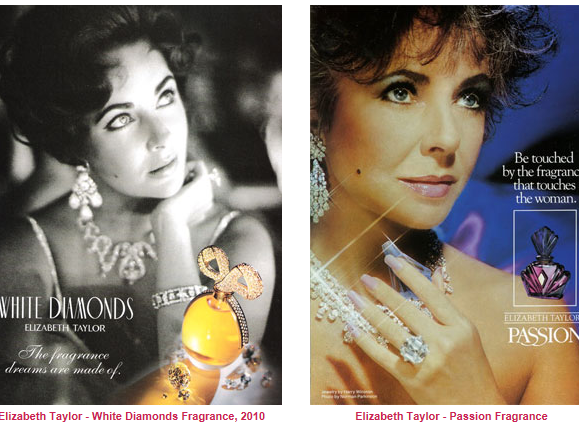

This personal culture relies on how convincing the actor is in their role, and the identity of the actor must be hidden in order to create the illusion that they are the total embodiment of the character that they are portraying. In certain situations it is the actor themselves who does this. Kevin Spacey explained in a 1998 interview with the London Evening Standard: ‘the less you know about me, the easier it is to convince you that I am that character on screen. It allows an audience to come into a movie theatre and believe I am that person’ (‘Kevin Spacey: The Unusual Suspect’). It could be argued that celebrities are not the faces of brands, but are instead representing themselves. Elizabeth Taylor once threatened to sue a cable company that was about to air an unauthorised TV film about her life and to do this she stated, ‘I am my own industry… I am my own commodity’ (Taylor cited in Hozić 205). When advertising a product, Taylor never used the name of a character that she had been playing in a film: they were always endorsed by her personally (see Figure 5).

Figure 5: 'Celebrity Endorsements' 2010

There is a marked difference here between Elizabeth Taylor and Daniel Craig, as when he is featured in adverts it is always as James Bond and never as himself. This makes the connection between the films and the products even more palpable as he is the brand and as such addresses the desire that is linked to the commodity. This also allows for more variety to be shown in the adverts that feature Daniel Craig as James Bond. It is possible to manipulate Bond’s image more as he is a character from a series of books and films. If it were Daniel Craig marketing the products and representing the brand, there would be more restrictions over what could and could not be done with regards to the advertising campaigns. This leads to different companies being able to use separate facets of the James Bond persona when marketing their products, but at the same time still being able to use the image of Daniel Craig. It is important to factor in that of course Daniel Craig is still at liberty to appear in adverts as himself and to not have his identity confused with that of James Bond. I am not suggesting that the audience are unable to differentiate between the two, but instead highlighting that in order to create a successful brand image it is necessary to make the gap between Craig and Bond as small and invisible as possible.

The brand is not something that is permanently fixed but is rather something that can exist in different, potentially infinite versions. In the examples that I have chosen, Bond appears in several different guises: dressed casually, depicted in a smart suit and also ready to shoot his gun at an assailant. Something that stands out when using a celebrity as the image for a brand, is how malleable that image is when moving from one product to the next. Daniel Craig does not advertise solely for Omega. As James Bond his image is also used for Sony Ericsson, Barclaycard and Sony. Here it is can be noted that ‘icons need not be attached to objects at all’ (Lash and Lury 15). This comes most clearly to the fore in a television advertisement campaign for International Women’s Day in 2011. The video consists of Daniel Craig standing in a smart suit in front of the camera while a voiceover from Judi Dench who played M speaks to him (‘James Bond star Daniel Craig in drag for International Women’s Day’). The most important aspect of this video is the number of times which Daniel Craig is referred to as James Bond. Right at the start Judi Dench asks, ‘we’re equals aren’t we, 007?’ before going on to reveal facts about the differences between women and men culminating in, ‘as a man you are less likely to be judged for promiscuous behaviour, which is just as well frankly’ (‘James Bond star Daniel Craig in drag for International Women’s Day’). This tongue in cheek comment leaves us in no doubt that who is being watched is James Bond and not Daniel Craig as Bond’s relationships within the franchise are often commented on. What is most important to note here is how Daniel Craig does not speak throughout the course of the video. He remains totally silent, his voice hidden behind the brand of James Bond. It is the values that Bond stands for and the personality traits that he holds which are reflected in the products that are being sold.

These traits are made particularly clear in a television advert by Sony for high definition television. Daniel Craig is in his James Bond persona, this becomes clear as he is sharply dressed and has the same cuts and bruises on his face that the character does in Casino Royale. The advert consists of James Bond standing still and steely faced as a succession of explosions go off around him. Even with debris flying towards, Bond remains stoic and simply dodges it or regains control of his stance when hit (‘Watch Daniel Craig in Advert for Sony HD TV’). Resilience is a quality of Bond’s that is taken up in many of the products that he is connected with. This article has illustrated how the use of a celebrity allows for the ‘forging of links of image and perception between a range of products’ (Lury cited in Moor 43). The purpose was to illustrate the emergence of branding as a part of a complex mediation between the brand and the spectator. What is important to note are the implications for the participation of consumers in the economy and also for consumer culture. In using James Bond as an example it enables us to see that products ‘are branded, they have a kind of unity in their relation to one another’ (Lury 2004 76). Due to this union it becomes increasingly difficult for the voice of Daniel Craig to be brought forward as all that can be seen or heard is James Bond.

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. ‘Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography.’ in Julia Thomas (ed) Reading Images. London: Palgrave, 2001. 54-62.

Bowlby, Rachel. Just Looking: Consumer Culture in Dreiser, Gissing and Zola, New York: Methuen, 1985.

Casino Royale. Dir. Martin Campbell. 2006.

‘Celebrity Endorsements.’ 2010. Web. 24 Feb 2014.

Coward, Rosalind. ‘The Look.’ in Julia Thomas (ed) Reading Images. London: Palgrave,2001. 33-40.

Featherstone, Mike. ‘Body, Image and Affect in Consumer Culture.’ Body & Society 16.1 (2010): 193-221.

‘Hand over your wristwatch 007.’ The Daily Mail Online. 2011. Web. 24 Feb 2014.

Hozić, Aida A. ‘Hollywood Goes on Sale; or What do the violet eyes of Elizabeth Taylor have to do with the “Cinema of Attractions?”’ in David Desser and Garth S. Jowett (eds) Hollywood Goes Shopping. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000. 205-222.

‘James Bond celebrates 50th Anniversary.’ The Daily Mail Online. 2012. Web. 24 Feb 2014.

‘James Bond star Daniel Craig in drag for International Women’s Day.’ the Guardian. 8 Mar 2011. Web. 24 Feb 2014.

‘Kevin Spacey: the unusual suspect.’ BBC. 2003. Web. 24 Feb 2014.

Lash, Scott and Celia Lury. Global Culture Industry: The Mediation of Things, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2007.

Latham, Alan and Derek P. McCormack, Derek P. ‘Moving Cities: Rethinking the Materialities of Urban Geographies.’ Progress in Human Geography (2004): 701-724.

Lury, Celia. Brands: The Logos of the Global Economy, London: Routledge, 2004.

Lury, Celia. Consumer Culture, Cambridge: Polity Press, 2011.

Moor, Elizabeth. ‘Branded Spaces: The Scope of “New Marketing.”’Journal of Consumer Culture 3.1 (2003): 39-60.

‘Omega and Bond.’ Omega Watches.com. 2014. Web. 24Feb. 2014.

Oumano, Elena. Cinema Today: A Conversation with Thirty-nine Filmmakers from Around the World. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2011.

Prince, Stephen. Digital Visual Effects in Cinema: The Seduction of Reality. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2012.

Quantum of Solace. Dir. Marc Foster. 2008.

Skyfall. Dir. Sam Mendes. 2012

‘The Bond Brief.’ Independent Online Solutions.2010. Web. 24 Feb 2014.

Thomas, Julia. ‘Introduction’ in Julia Thomas (ed) Reading Images. London: Palgrave, 2001. 1-11.

‘Watch Daniel Craig in Advert for Sony HD TV.’ the Guardian. 15Oct 2008. Web. 24 Feb 2014.

Email: luminary@lancaster.ac.uk